winter/spring 2026

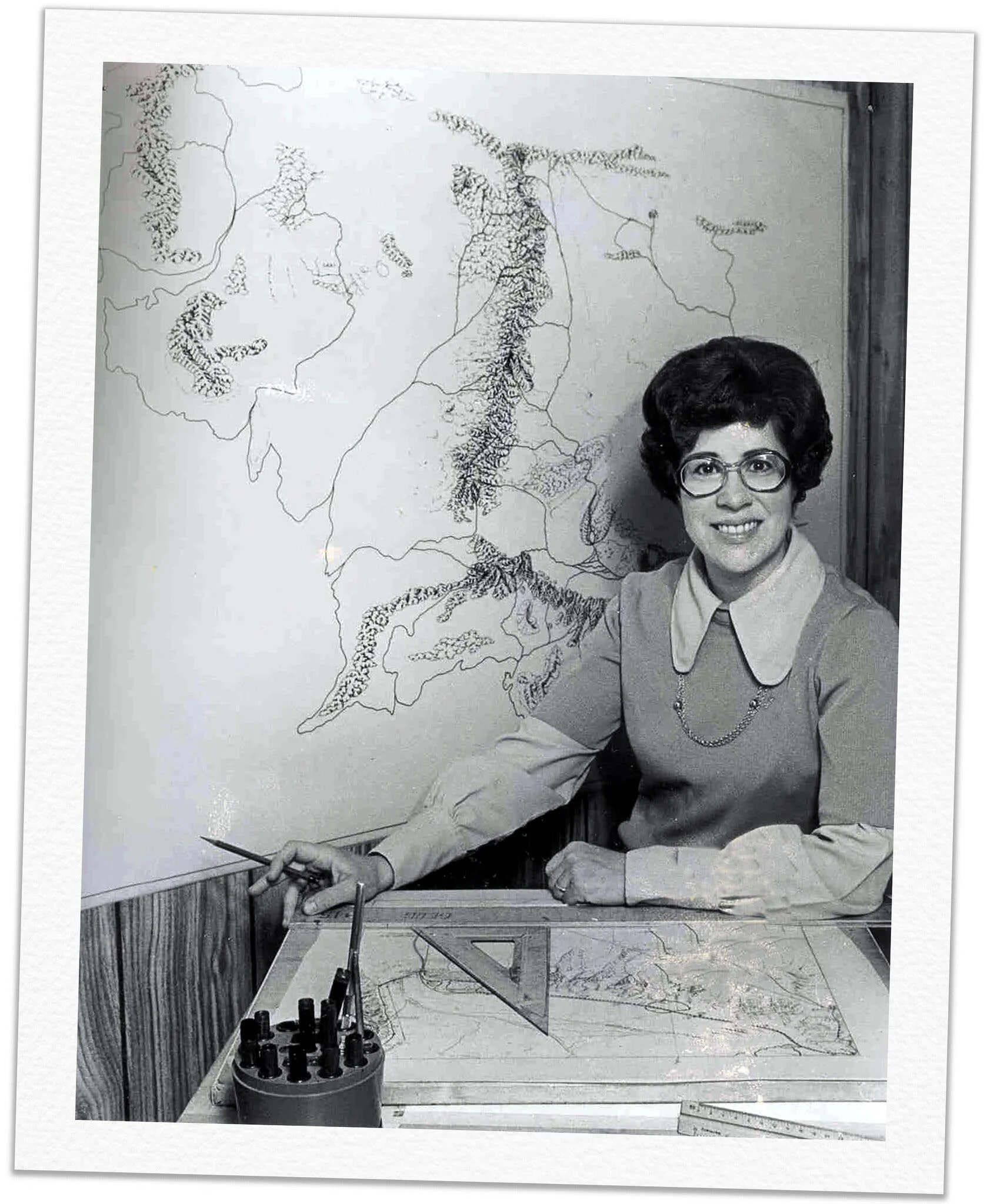

Karen Wynn Fonstad, author of The Atlas of Middle-earth. Courtesy Carl Plotz via Fonstad family.

Contents

Places Books Call Home: The Evolution of the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay Library

by Alexa Van Laanen

“We’re Here!” Hard Truths, Indigenous Voices, and the Commemoration of Oneida Resilience in Northeast Wisconsin

by Stephen Kercher

The Sisters of the Holy Cross at Bay Settlement

by Cletus Delvaux

The Wisconsin Cartographer Who Mapped Tolkien’s Fantasy World

by Rob Ferrett and Beatrice Lawrence

At Riverview Sanitarium

by Kay McCabe Moore

I Have Returned: An Excerpt from Red Arrow Across the Pacific: The Thirty-Second Division during World War II

by Mark D. Van Ells

An Interview with Mark D. Van Ells

by Jacob Acker-Law, Reece Bertrand, and Crystal Luedtke

From the Editor

We have exciting news to share. One of my long-term goals as editor-in-chief has been to digitize the entirety of the Voyageur catalog, as has been done with the Wisconsin Historical Society’s stellar Wisconsin Magazine of History. As you can probably imagine, with over forty-one years of content in our ever-growing collection, that’s a monumental task. We’ve engaged in numerous conversations about how to achieve this goal over the past several years, and I am thrilled to announce that this project is now underway. The digitization of the magazine—which will be hosted by the UW-Green Bay Library—will provide searchable access to hundreds of articles, interviews, reviews, and other content for both researchers and lovers of our region’s history alike. The completion of this digitization project is a major achievement in the history of Voyageur and will further our core mission of preserving our region’s history for generations to come. We will make another announcement on our website, social media, and in the print magazine when the digital archive is live and available for your use.

For their support of this project, we would like to offer our sincere thanks to: Deb Anderson, coordinator of the UW-Green Bay Archives and Area Research Center; Paula Ganyard, director of the UW-Green Bay Library; Ryan Martin, dean of the UW-Green Bay College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences; and the board of the Brown County Historical Society.

I will close with both a farewell and welcome. Dan Kallgren, the magazine’s associate editor from 2019 to 2024, retired from UW-Green Bay last May after over thirty years of dedicated teaching and service. Art director Addie Sorbo and I loved having worked with Dan, who brought an endless optimism and levity to our collaborative effort. Dan will certainly be missed, but he is now enjoying a well-earned retirement in Marinette. We are delighted to announce that our new associate editor is Heidi Sherman, professor in Humanities and History at UW-Green Bay. We are excited for Heidi—who spearheaded the move of the wonderful Viking House to UW-Green Bay and coordinates the annual Midwest Viking Festival held on our campus every fall—to be joining the Voyageur team. Her personal introduction to our readers follows below.

We hope that you enjoy this issue of Voyageur.

Eric J. Morgan

Editor-in-Chief, Voyageur: Northeast Wisconsin’s Historical Review

Associate Professor, Democracy and Justice Studies and History, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay